In Southeast Asia, democracy is on the backfoot. Why is this so? Because elections are manipulated through fraud, coercion, or institutional bias that distorts outcomes to favour certain political actors.

Put simply, the exercise of competitive multi-party elections is being carefully calibrated by an entrenched political elite to ensure they remain in power.

When this happens elections simply serve to allow people to cast their ballots but not necessarily allow the results of the polls to reflect their will.

In this context, taking action to address these manipulations, uphold the integrity of elections, and ensure genuine democratic processes that truly represent the voices of the people has become more necessary than ever.

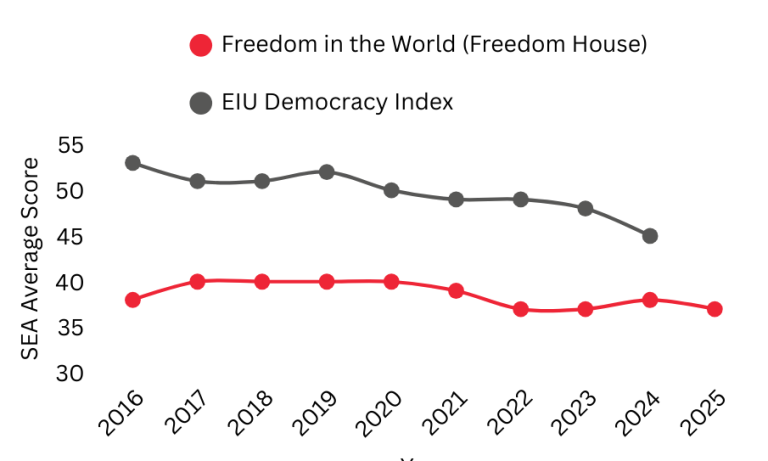

Across Southeast Asia, global democracy indexes, such as those by The Economist and Freedom House, reflect a generalised democratic regression in Southeast Asia since the late 2000s and early 2010s.

Regional trends show the representative feature of elections have been weakened from the concerted efforts by respective ruling regimes to manipulate its results in various forms: party cartels that prioritise power-sharing among former rivals; violence, legal manoeuvring, administrative tactics, and media control to weaken opposition parties; party-hopping that disregards voter choice and leads to government changes without elections; military takeovers that topple democratically elected governments; and unchecked judicial intervention that grants courts excessive power over election outcomes and constitutional matters.

Indonesia’s general elections after the collapse of the New Order regime exemplify how the dominance of party cartels – political alliances that consolidate power among a select group of elites – has severely restricted real political competition. Major political parties function as oligarchic, closed networks, turning elections from a genuine contest for political representation into a competition among insiders. This dynamic not only erodes public trust in political processes but also entrenches elite dominance, further deepening democratic stagnation.

Concerns around manipulated elections extend beyond Indonesia. Across the region, political parties with a strong grip have tilted elections in their favour.

Cambodia’s ruling party, the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), has systematically manipulated outcomes by stifling opposition parties such as the Cambodia National Rescue Party and, more recently, the Candlelight Party. Mechanisms employed include enacting restrictive electoral law amendments, using judicial and administrative tactics to disqualify candidates, employing violence and intimidation, and tightly controlling the media. This reduces elections to a rubber-stamping exercise to certify the victory of the CPP while keeping a multi-party system to make the win legitimate.

In Thailand, traditional ruling regimes use judicial interventions and electoral commission rulings to undercut opposition parties, creating an uneven playing field. The Constitutional Court has been instrumental in disqualifying opposition candidates and dissolving political parties critical of the establishment, as seen in its rulings against the Future Forward Party in 2020 and the Move Forward Party in 2024. These decisions, coupled with electoral commission interventions, have severely manipulated the outcomes of political competition, undermining the legitimacy of Thailand’s electoral process.

Meanwhile, in Myanmar, the military and electoral institutions have actively dismantled elections. The military’s refusal to recognise the 2020 election results and subsequent coup in 2021 have erased any remaining semblance of democratic competition. Even before the coup, election laws were manipulated to exclude opposition voices, and voter suppression tactics disproportionately targeted ethnic minorities.

In Singapore, the First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) electoral system and the regular redistricting of opposition voter strongholds consistently deliver a disproportionate number of ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) MPs to the parliament. Despite growing vote shares for the opposition parties, they consistently receive a much smaller proportion of seats compared to their voter support. For instance, in the 2020 election, opposition parties garnered 40% of the vote but only secured 13% of the seats, while the ruling PAP received 60% of the vote and took 87% of the seats. This disparity undermines the representativeness of the voter sentiment by not translating the opposition’s voter share into an equitable number of parliamentary seats.

In Malaysia, the existence of party hopping subverts voter choice. The example of the 2020 Sheraton Move, where party defections toppled the elected government without a new vote, shows how party-hopping can manipulate election results. While the Anti-Party Hopping Law was enacted in 2022 to prevent individual MPs from switching parties, it does not cover entire parties, allowing backdoor changes in government. In response, larger coalitions have formed to prevent instability, but this risks diluting multi-party democracy and distorting the electorate’s will.

These examples illustrate how elections in the region are being systematically subverted and manipulated to ensure that ruling regimes stay in power.

As a consequence, elections are failing to deliver genuine democratic progress. And when elections are perceived as manipulated – because they lack true competitiveness – citizens become disillusioned.

The forms of electoral subversion have been widely studied and identified; what is now needed is a coordinated multistakeholder approach from national and international actors to call out these subversions, promote electoral integrity, and work towards building a sustainable and truly democratic system for the future.

Otherwise, elections run the risk of becoming meaningless.