For the coming 2025 general election, collective voter support needs to surpass 40% for opposition parties to have a tangible impact on the political landscape of Singapore.

Although the First Past The Post (FPTP ) system does not guarantee a correlation between voter percentage and seat allocation, an opposition vote share that is higher than 40% would put pressure on the system and call out the disparity gap in seat distribution further.

As of 1 February 2025, 2,758,095 Singapore citizens are eligible to vote in the widely expected 2025 general election, the Elections Department (ELD) announced on 24 March 2025.

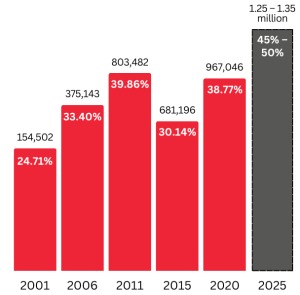

This means that, to reach the 40% mark, over 1.1 million voters need to vote for opposition parties if the percentage is to match the highest percentage (40%) of votes opposition parties received in the history of Singapore’s elections in 2020.

Hence, in 2025, 1.25 to 1.35 million people voting for the opposition – 45% to 50% of the electorate – will be a move in the right direction.

In the 2020 election, about 40% of voters (967,046) voted for opposition party candidates, but this delivered only 10 seats (13% of the 93 elected seats). Instead, the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) secured just over 60% of the vote – 1.5 million – but gained 83 of 93 elected seats (87%).

This disproportionality is not a new phenomenon.

In 2015, when all seats were contested, opposition party votes made up around 30% of the total (681,196 votes), but opposition parties only secured 6 seats (6.7%).

In 2011, when 82 of 87 seats were contested, opposition parties secured nearly 40% of the votes (803,482 votes), but this also delivered only 6 seats (6.9% of the total elected seats and 7.3% of the seats contested by opposition parties).

In 2006, when 47 out of 84 seats were contested, 31% of the vote shares (375,143 votes) resulted in only 2 of 84 elected seats (2.4% of the total and 4.3% of the contested seats).

As Singapore’s 2025 general election approaches, it is clear that the First-Past-The-Post voting system will continue to heavily favour PAP. In addition, the regular redrawing of boundaries has built momentum around public discussion on the unfair impact on opposition parties.

Despite these challenges, there have been periods when opposition parties have successfully tapped into Singaporeans’ frustration with the ruling regime. Over the years, the opposition has gained significant growth in support as they begin to contest all seats in a given election.

While the vote share between different opposition parties varied, between the 2001 and 2011 elections, collective opposition votes gradually increased, culminating in a 15-percentage-point rise across the three elections (2001, 2006, and 2011). After a dip in 2015, the opposition rebounded with a 9-percentage-point increase in votes in the 2020 elections.

Overall, since 2001 to 2020, the share of votes for opposition parties has grown by 14 percentage points. Hence, a rise in 6% to 11% in opposition votes in 2025 will continue the growth momentum and keep the pressure on electoral reform.

The entrenched structural barriers of the FPTP system may yet prevent 50% of opposition party votes from translating into a proportionate 50% share of elected parliamentary seats.

It is also not to be unexpected that a lower percentage of overall vote share for the opposition might not negate some opposition parties scoring a better electoral return than others. After all, different opposition parties will differ in the volume of voter support they attract.

Nevertheless, what an increase in voter support for opposition parties overall can do, is put pressure on an electoral system which is seen as being largely unrepresentative in returning opposition party candidates into Parliament.

A large opposition vote share can build momentum and pressure to take into account the perspectives and voices of the opposition parties and the broader electorate.